Blick Bassy – A Time to Remember

Feature

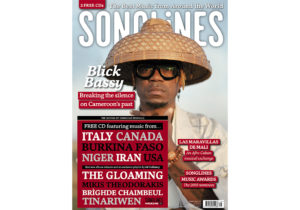

As part of Songlines Encounters Festival 2020, singer-songwriter Blick Bassy will perform music from his latest album 1958. Daniel Brown speaks to the Cameroonian musician about breaking the silence on France’s colonialist treatment towards his country’s independence heroes. This is an extract of a feature published by Songlines magazine in May 2019.

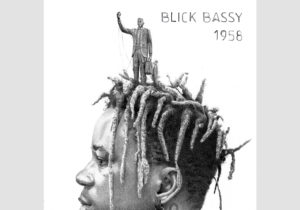

Composed in France’s south-west village of Saint-Aubin-de-Branne, Blick Bassy’s latest album 1958 is an indictment of the savage killing by the French army of one of the unsung heroes of his native Cameroon, Ruben Um Nyobé.

‘I see no contradiction in living in the belly of the beast,’ he says flashing his disarming and ubiquitous smile. Yet, one senses he’s ill at ease. After all, the cost of Cameroon’s struggle for independence is one more unadmitted skeleton in the cupboard of France’s colonial past. Figures fluctuate wildly from 20,000 to 120,000 Cameroonians killed, with historian Meredith Terretta estimating that the 1956-1964 era yielded up to 76,300 victims. This inability to even admit there had been what reporter David Servenay calls “an all-out war” rankles with the musician. ‘We’re close to 60,000 Cameroonians living here and I don’t think there’s one of us who doesn’t still feel that hurt.’

‘I see it as my duty to sensitise both the French and the Cameroonians to their own history, warts and all’

‘I see it as my duty to sensitise both the French and the Cameroonians to their own history, warts and all. That’s why 1958 is more than a record, it’s a workshop. I sing in my native Bassa, only spoken by two million people at home, so I translate my messages during concerts. I’m a bit like Um Nyobé: I try to be an mpodol – one who carries the word to his brethren. That’s the title of one of my songs, where I denounce our leaders for not dignifying his memory.’

Bassy’s links to Ruben Um Nyobé are both ideological and personal. The trade unionist came from Boumneybel, a village three kilometres from where the musician’s maternal grandparents lived. Born in 1913 when Cameroon was a German colony, Um Nyobé’s two decades of union and French anti-colonial struggles propelled him to the head of the nation’s independence movement. Forced into hiding in Bassa territory in 1955, he was mowed down in 1958, dragged through the villages and buried in concrete by the French military. ‘At the time, my mother and her father had to spend 18 months hiding in the forest. The military were capturing and torturing people at random to discover where Um Nyobé’s hideout was. The stigma around the resistant’s death and memory then took Kafkaesque proportions. ‘It’s one of the reasons for my making this album. Pronouncing Um Nyobé’s very name was an offence in Cameroon until 1991! During my research for this record, my grandfather would still whisper his story for fear of being overheard.’

‘I was struck by Um Nyobé's visionary speeches, they still resonate in our divided country’

In Bassy’s years of schooling in Mintaba and Yaoundé, Um Nyobé and his followers were labelled agitators or simply airbrushed from his history classes. ‘Worse, everything associated with the Bassa community was negative because his resistance centred on our region. We were all branded terrorists, violent and irresponsible. Until today, we are stigmatised. That was the second reason I had to bring out this album.’

A third motivation resided in Um Nyobé’s general philosophy. A charismatic orator, he impressed the UN assembly with his calls to unify an independent Cameroon under a moderate ten-year plan. ‘I was struck by his visionary speeches, they still resonate in our divided country. They denounced the communal divisions that are tearing us apart, they insisted on reconnecting with our traditions and history to go forward. In songs like Ngui Yi (‘Ignorance’) and Sango Ngando, I sensitise Cameroonian youth to Um Nyobé’s sacrifice and their responsibility to honour our heritage. This generation must defy foreign imported culture and design their own role models and paths, like he did.’

‘This generation must defy foreign imported culture and design their own role models and paths, like he did’

Following the success of the album Akö released in 2015, 1958 stands out as the Cameroonian’s most personal and engaged work to date. ‘We’ve been waiting too long to shed light on Um Nyobé’s assassination,’ confides Bassy. ‘Yet the French have promised to release archives on such crimes ever since Jacques Foccart was the the Elysée’s Mr Africa. And it’s not just Um Nyobé’s assassination, there’s also his successor Félix-Roland Moumié, killed two years later. The French were ruthless and really decapitated a leadership which could have made a difference.’

To drive his message home, Bassy turned to South African Tebogo Malope to direct the album’s first video clip for Ngwa. Set in the breathtaking mountains of Lesotho, the award-winning director offers a dense homage to Ruben Um Nyobé with a smattering of Pan-African references – from Matigari by Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong’o to the contribution by South African resistance figure Solomon Mahlangu whose dying words were ‘My blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom.’ In the video’s final scene Bassy / Um Nyobé’s dead body sprouts the roots, trunk and branches of a new dawn. Just another mirror the musician-philosopher leaves us with, reflecting a generation-old balancing act between death and rebirth, loss and resistance.

The full interview was published in Songlines magazine issue 147 (May 2019).