An introduction to Philip Cashian’s Volvelles

Feature

On Sat 11 Dec, leading composer and clarinettist Mark Simpson performs a programme of clarinet and electronics/loops featuring world premieres, including Atma by Zoë Martlew and Volvelles by Phillip Cashian, and contemporary classics by Steve Reich and Jonathan Harvey. Ahead of the concert, Benjamin Poore introduces Cashian’s piece, inspired by rotating paper-made medieval calculators found in early books.

Philip Cashian, Volvelle

for B-flat clarinet and fixed media

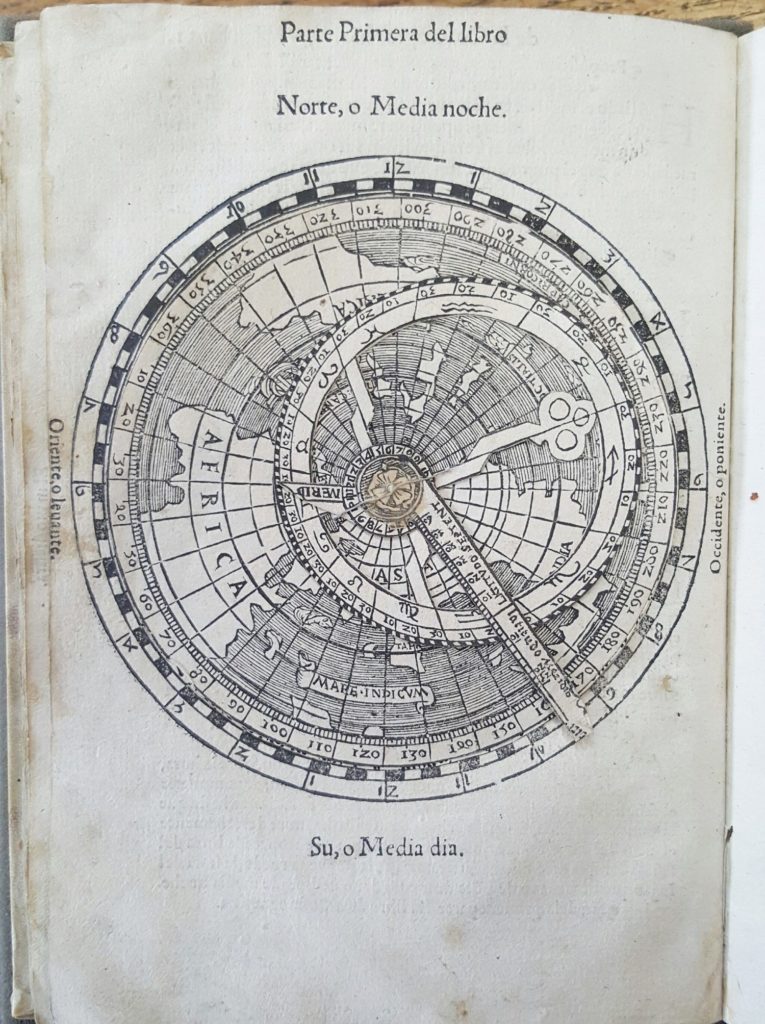

A volvelle is an intricate paper chart, a rotating medieval calculator found in early books. They are a relative of the astrolabe – a set of superimposed metal sheets that could be configured for astronomical or navigational purposes. 16th-century books would come with the parts for a volvelle included, so that the purchaser could assemble these delicate computational sculptures themselves. As the parts turn, they align stars, numbers, symbols, and ideas – depending on their purpose, before shifting out of sync again.

Volvelles, Philip Cashian’s piece for Mark Simpson, works along similar lines. It is a piece that slowly accumulates and gains momentum, then, as with these paper machines, interlocking its constituent parts, before winding down at the end.

The piece has had a long gestation – Cashian and Simpson started experimenting with ideas and fragments in a session over three years ago; in this respect it belongs to another world. But there’s no doubt that Covid’s impact on musical life has given it a certain sharpness. For so long the absence of live music threw us back onto recordings and performance mediated by technology. As with all the works in Simpson’s programme, Cashian brings these modes together – sometimes they synchronise uncannily, and sometimes observe their own logic. ‘I’m very interested in mechanisms and machines’, Cashian tells me. They provide clear recognisable patterns, he explains, that become ‘a springboard for invention.’

It is Cashian’s first piece using electronics – he was especially grateful to Phil Dawson, also based at the Royal Academy of Music, for lots of technical help. Cashian likes ‘the idea of the cogs turning . . . making the sound move around the room’, promising an immersive, dynamic sonic environment alongside Simpson’s vivacious live performance. At points, the audience may feel like they are part of the intricately spinning machinery of a volvelle themselves.

Volvelles are an interstice of many modes of thinking and being. An innovation from the Middle East, they also represent pinning cultures together. They were used by astrologers, for navigation, to calculate important dates in the Christian calendar – and for occult purposes. They suggest the meeting of natural and unnatural forces, human and celestial scales, something echoed in Cashian’s combination of artificially-engineered and live sound.

The clarinet too suggests the volvelle’s fusing of elements and worlds. It feels both archaic and modern, comprised of both organic (wood) and inorganic (metal) elements in its structure and mechanism, warmed by human breath but residually mechanical in the clacking of its keys (especially in a piece as virtuosic as Volvelles). ‘There’s something almost steam-powered about the way it looks’, Cashian says.

Simpson’s distinctive, charismatic playing has been an inspiration for all the composers writing for this concert. ‘The sheer virtuosity struck me’, Cashian tells me. ‘Hearing him play takes you to a kind of transcendental state.’ Cashian recalls hearing Simpson play the Magnus Lindberg concerto, and his extraordinary improvised cadenza. But one aspect of Simpson’s playing in particular has found its way into Volvelles. ‘Mark is brilliant at playing high notes really really quietly’, Cashian says. Plenty of these velvety entries have found their way into the piece, especially in its first few minutes. The clarinet’s special ability to negotiate rapid changes in register – leaping from top to bottom seamlessly – is another key feature of the piece.

Volvelles, like its namesake, bridges magic and mechanism. Recorded sounds sometimes echo and sometimes offset the skittering spontaneity of the live clarinet; the former have an especially distended, strange quality – Cashian used the pre-synthesised sounds of marimbas and clarinets playing wildly out of their usual registers from the music notation software Sibelius to invent the electronic track. Mechanical reproduction meets shamanic virtuosity before dissolving into silence.

Philip Cashian official website

BENJAMIN POORE